Margaret knew. She had two ambitions for Venice. The first was satisfied on Tuesday evening, with the help of Fabio and his gondola Sebastiano (or possibly Ginevre). The other was to go to Murano.

Murano is a separate largish island in the Venice lagoon—or, to be precise, it’s a group of islands separated and joined by canali and bridges. (It has its own Canale Grande.) The thing about it is, it’s a good half-kilometre from Venice itself, and therefore a useful place to store valuable involuntary arsonists.

A fire in Venice must be hellish: bad enough at the side of a canal, where at least the fire brigade can have reasonably quick access, but unimaginable anywhere down those narrow twisty mazes of little passages, all alike. So an offshore island is an ideal place to banish all your glassmakers along with all their dangerous furnaces, which is what Venice did in the 13th century. There, they flourished and established the world-famous Murano Glass industry (though actually, Murano glass had begun to become famous four centuries earlier). Margaret’s ambition was not only to go there, but to buy some!

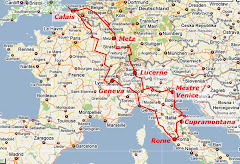

We hopped on the train and crossed the causeway to Venice (the orange strip c

oming in from the left in the map—click on it to see it full-size), and caught the No. 41 vaporetto heading west, because it goes the long way round, a sort of "sea cruise" via the Canale della Giudecca which separates “mainland” Venice from that long skinny east-west island to the south. The route goes round Venice’s “industrial” areas, as well as by the international port, where some HUMUNGOUS liners come in …

oming in from the left in the map—click on it to see it full-size), and caught the No. 41 vaporetto heading west, because it goes the long way round, a sort of "sea cruise" via the Canale della Giudecca which separates “mainland” Venice from that long skinny east-west island to the south. The route goes round Venice’s “industrial” areas, as well as by the international port, where some HUMUNGOUS liners come in …Murano (being an artisan district) has little of the grandeur of Venice itself (though we understand that the cathedral, which we didn’t see, is pretty good). And it turned out that, on a Wednesday afternoon (it’s quite a long trip from Ferrovia), it had little of anything else, either, at least, not when we were looking for lunch—early closing day, you see! We wandered around a few streets (the canal-side paths are wider than in Venice), but didn’t find many food places, and none that were open, until we stumbled across Trattoria al Frati on Murano's own Grand Canal.

Fortified by food and drink, we strolled round the streets again, this time with different purpose: the Hunt for Glass. There was no shortage of glass shops, but none jewellery that Margaret liked, until we found Gioielli R.T. (“Jewels Rossetto Tiziano”), where she bought a necklace and two pairs of earrings (one pair a close match to a necklace she already had—clever girl!), while Don bought a silver-nibbed glass pen.

A visit to Murano wouldn’t be complete without a visit to a glass factory, except that, on Wednesday afternoons, they all close. Well, almost all: turned out that the Formia factory was still open (just) and we spent a good half hour watching some skilled workers playing with fire—the Venetians’ nightmare!

Strolling back to the boat landing, we saw several examples of the amazing glass sculptures that dot the Murano townscape. The one illustrated is in one of Murano’s relatively substantial open spaces. We also spotted, quite by chance, the Church of St Peter the Martyr (Peter of Verano), and went in. It dates from the mid-1300s (fine frontage from the early 1500s), and hosts some good murals, several Tintorettos, and a fine Bernini, but the best reason to include it in your own tours is its “ligneous sacristy”, which is to say, the Woo

den Vestry, whose four walls are lined with the most brilliant wooden panels and reliefs, carved for a local school in the 1560s and rescued from the school’s demolition by the parish priest in 1815.

den Vestry, whose four walls are lined with the most brilliant wooden panels and reliefs, carved for a local school in the 1560s and rescued from the school’s demolition by the parish priest in 1815.Back on the vaporetto, we continued on route 41, past San Michele island, rather lovely with the pink walls, white pillars, arches, and cupolas, and green cypresses of the Cimitero, which does indeed mean “cemetery” (and makes up the whole island—see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Michele ), round the northern shores of Venice, and down into the Canale di Cannaregio, which leads back into the Grand Canal. We got off at Giglie, the stop before Ferrovia, and walked towards the station along the Rio (street) Tera Lista di Spagna, admiring the shops and stalls selling antiques, carnival masks, ceramics, jewellery, artwork, toys—and hand-made, hand-painted, wooden sculptures of mediaeval-style clowns (buffi), one of which we stopped to buy.

We wound up in the Piazzale Roma, a small piazza next to Ferrovia, where we chose the Ristorante Roma for our last dinner in Venice, at a candlelit table next to the Grand Canal. Because of the location (and its romantic eventide views), the prices were higher than we’d got used to in Venice. In fact, the prices, the service, and the food, all generated protes

ts in the few web reviews we’ve since read; but speaking for ourselves, we found the waiters very friendly, the food and wine good, and the service excellent. Perhaps our superior experience, as compared with the Internet reviewers, came from the obvious pleasure we showed in engaging with the waiters (showing genuine interest in Venice, and in the problems of fires in particular), and our willingness to try speaking Italian rather than English.

ts in the few web reviews we’ve since read; but speaking for ourselves, we found the waiters very friendly, the food and wine good, and the service excellent. Perhaps our superior experience, as compared with the Internet reviewers, came from the obvious pleasure we showed in engaging with the waiters (showing genuine interest in Venice, and in the problems of fires in particular), and our willingness to try speaking Italian rather than English.So our last day in Venice ended happily for us both, and it was with a little sadness that we got onto the train for Mestre for the last time—vowing, as always when we visit places and fall in love with them, that we have to go back …

No comments:

Post a Comment